Amateur radio continues to connect the world

U-M’s amateur radio club, headquartered in ECE, offers engineering challenges and a chance to network with students, faculty, staff, alumni, and strangers both on the other side of the world and those orbiting it.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Before iMessaging, email, and Snapchat, there was amateur radio.

Amateur radio or “ham radio” has been connecting people from all over the world for more than 150 years. The University of Michigan Amateur Radio Club (UMARC) was founded in 1913, and it continues to provide students – as well as faculty, staff, and alumni – opportunities to familiarize themselves with the concepts, techniques, and applications of practical radio communications.

“You can do it for fun. You can do it for education. You could do it for the public good. You can help groups like the Red Cross, things like that. And we do all of those things,” says Don Winsor, the EECS Departmental Computing Organization Coordinator who provides IT support to the club.

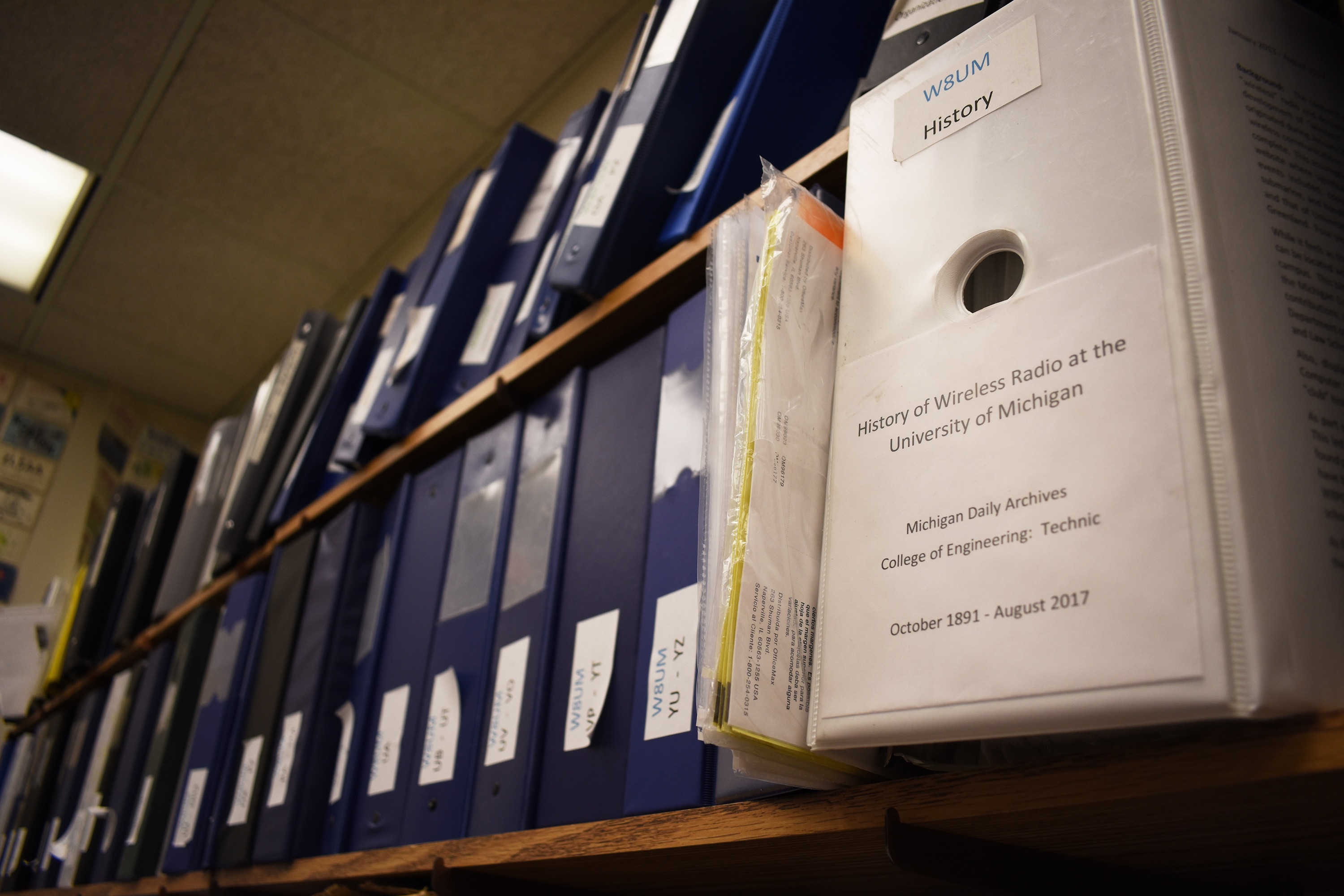

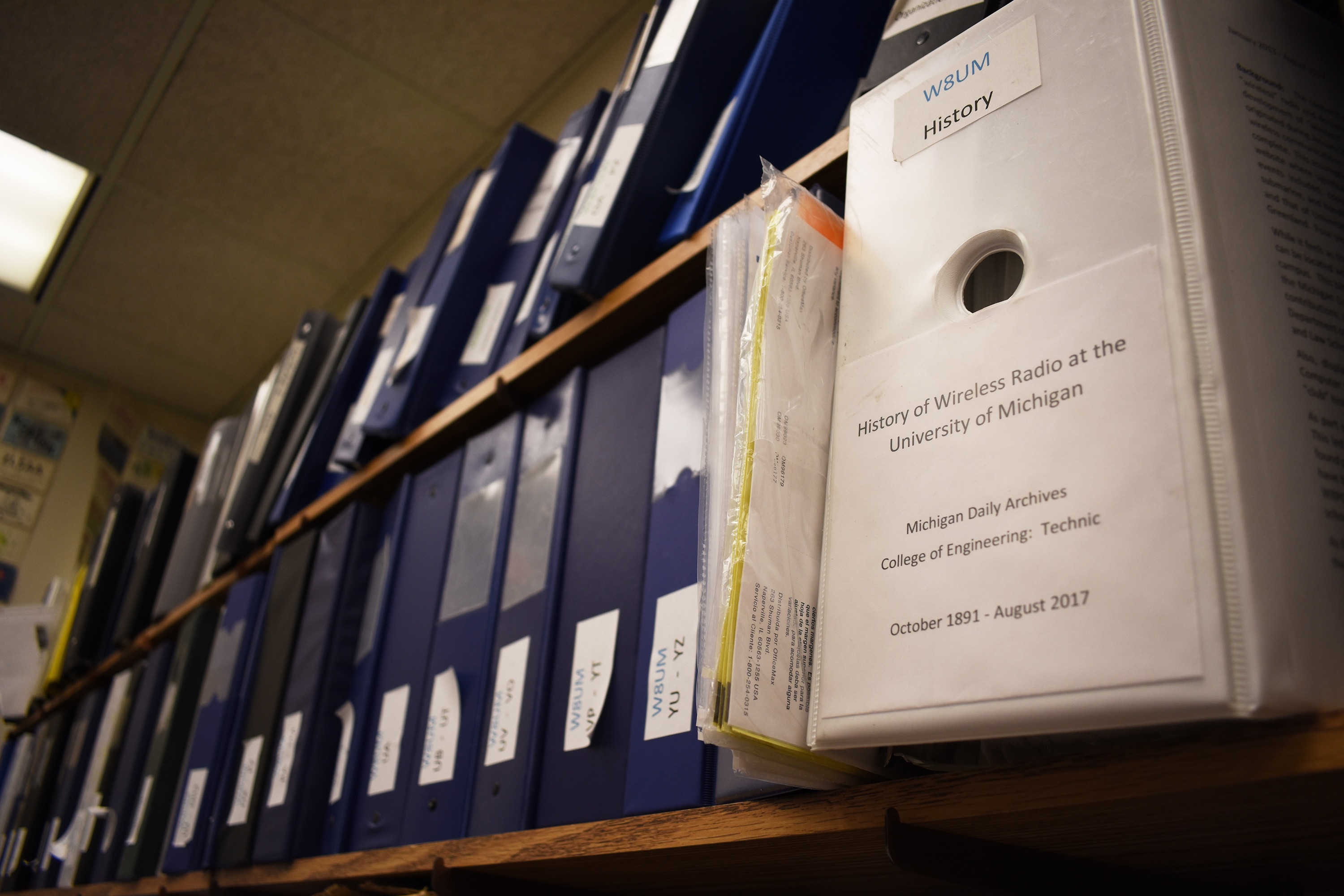

UMARC has its own station and a system of antennas, which are housed at the EECS building. Known by its call sign “W8UM,” the station’s equipment includes three HF transceivers and four VHF/UHF transceivers. The main antenna, roughly 40 feet square, is a rotating multi-band SteppIR antenna designed for the HF radio spectrum: 54 MHz – 7 MHz. For the VHF/UHF frequency (144 MHz band and 440 MHz band), W8UM operates a pair of circular, polarized, antennas for satellite communications. With these antennas, individuals can communicate via voice and Morse code, or they can send images using slow-scan television. They can also use a computer to send digital tones, such as PSK or FT8. For “local” communications, W8UM operates a radio repeater with EchoLink® connections housed in Weiser Hall.

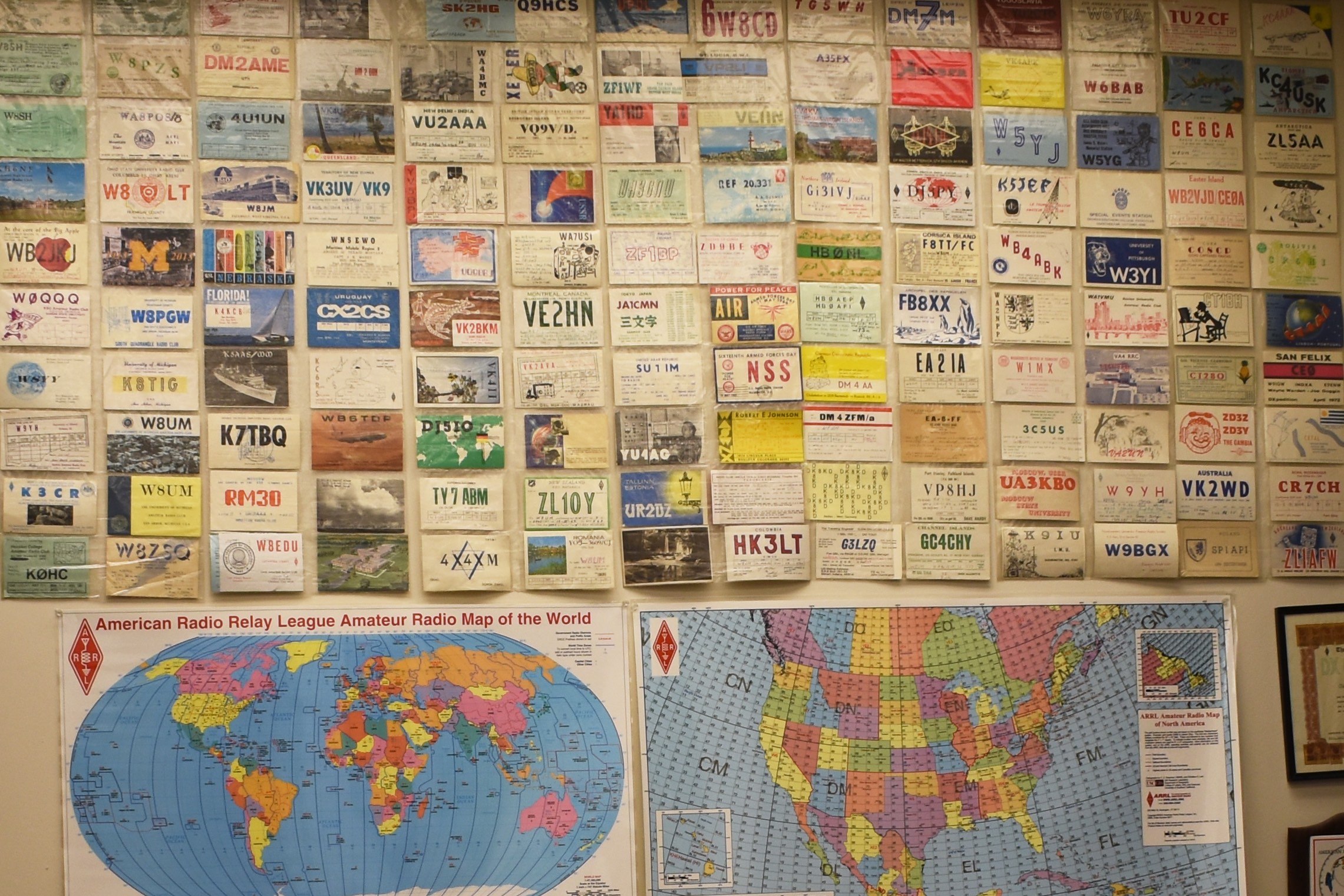

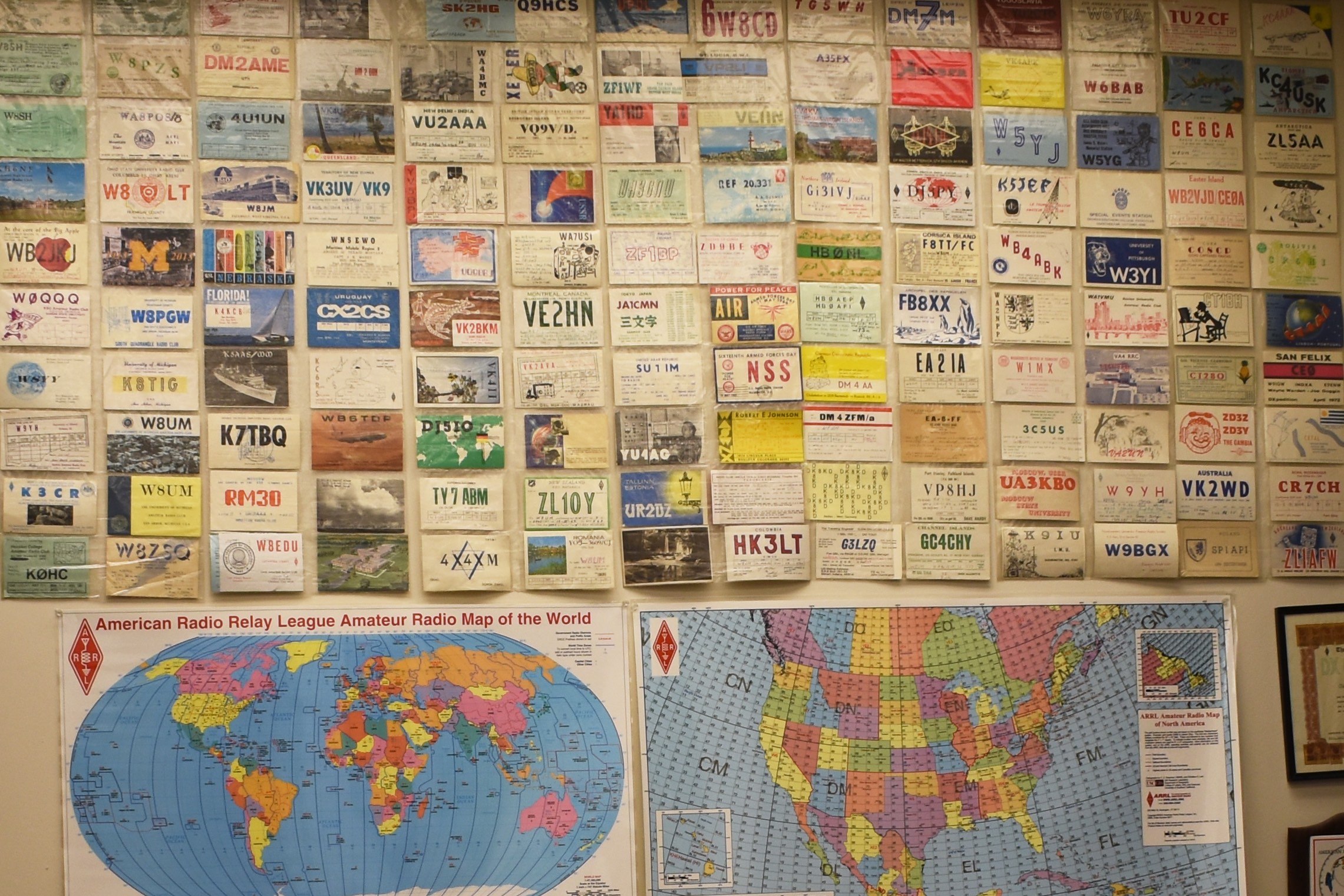

While atmospheric conditions, elevation, antenna characteristics, and environmental surroundings can all affect signal, UMARC’s powerful equipment amplifies the possibilities for students to communicate with people from all over the globe.

“You can go to the hobby store and get a radio that’ll work over short distances, but if you want something that’ll operate for miles, you need this technology,” Winsor says.

Enlarge

Enlarge

The W8UM station has born witness to several significant moments in history. It received communication of the sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, which is considered a critical event that helped bring America into World War I. The station also allowed U-M geology professor, William H. Hobbs, to communicate his observations about the climate and geological formations of Greenland during his expeditions there. In addition, the station handled radio messages for the Byrd expedition to Antarctica – a U.S. Navy operation that occurred from 1946-1947 with the goal of photomapping the area to eventually construct a research base. Thanks to the W8UM station, Hobbs and Byrd were able to communicate directly, which marks the first ever communication between the North Pole and the South Pole.

But one of the station’s most famous contributions to the university itself happened before the club was even formed.

Enlarge

Enlarge

In 1903, Floyd “Jack” Mattice – a U-M student and ham radio operator – broadcast the historic October 31st away football game between Michigan and Minnesota, where a reportedly suspicious Fielding Yost brought a five-gallon jug to ensure clean water for his team. Yost accidentally left the jug behind, but when he asked for it to be sent to him, he was told that if he wanted it, his team would have to win it back. The competition for the “Little Brown Jug,” the oldest “trophy” in college football history, was born.

Mattice telegraphed the events of the game play-by-play to the telegraph operators on campus, who announced the events of the game to 5,000 students in University Hall. It was the first time that Michigan students could hear a football game “live” as opposed to reading about it the following day in the Michigan Daily, and it was among the earliest instances of sports broadcasting.

Today, despite cell phones and the internet, there are still many relevant applications for amateur radio.

“During natural disasters, we may lose electricity for a prolonged period of time, or we may lose cellphone towers, and then the ability to communicate is disrupted,” says John Palmisano, a station manager for W8UM. “With amateur radio, our transceivers can be operated using a car battery or solar cells, and as long as we can suspend two wires in a tree, we can often make a radio contact.”

Due to the close proximity of the Fermi Nuclear Reactor and the transportation of hazardous material along the adjoining expressways, amateur radio operators are often called upon to assist if an emergency might occur. When cell phones go down, responders rely on satellite communication. If that were to fail, it’s up to ham radio operators to relay information.

“The two things they worry most about in this town are a severe weather storm or some kind of accident with hazardous materials where they would have to set up a shelter in a school gym,” says Winsor. “If phones aren’t working, how else would you communicate with the shelter, especially about things like special medical needs?”

Enlarge

Enlarge

Reid DesErmia, a junior in EE, became interested in the emergency communication applications of ham radio after serving in the military. DesErmia, a U.S. Navy veteran, served two deployments on a destroyer as a Radar Technician.

“Not only did we use radio to talk to each other, but we also used it for data and tracking,” DesErmia says. “All our ships were tracked on maps using radios, and you can still do that with ham radio. After I got out, I went and got my amateur license so I could continue to use the technology.”

DesErmia is current a member of Washtenaw RACES – the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service, which provides emergency radio communication for the county – and SKYWARN, the National Weather Service program for severe storm spotters. He also enjoys volunteering for events like marathons and bike races, where radios are used to track the progression of the race and call for assistance if needed.

Amateur radio has other useful applications. On campus, practical use of ham radio is used during balloon launches and recovery, projects involving remote environmental monitoring, cubesat missions, and other space-related projects. For instance, UMARC aided MRover in improving their communications, for places where rovers have to operate generally don’t have good cell service.

“I joined UMARC, because it has the ability to link with amateur radio clubs from other universities to tackle projects using modern technology,” says student president Kit Ng, an undergrad in ECE. “You can do much more with it than listening to music over the air. Radio amateurs are often at the forefront of engineering new protocols and more efficient forms of communications.”

Radio amateurs are often at the forefront of engineering new protocols and more efficient forms of communications.

Kit Ng, ECE undergrad and student president of UMARC

In addition to the practical uses, members say ham radio is appealing because it’s fun.

“There is a fascination with the equipment and there is the fascination that you don’t know who is going to hear your radio signal,” Palmisano says. “They could be 20 miles away or on the other side of the world.”

Or they could even be from outside the world.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Tony England, the Dean of the College of Engineering and Computer Science at U-M Dearborn and Professor of ECE, is a member of the club and a former NASA astronaut. He was flying a mission on the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1985 when he picked up a call on his amateur radio. The caller was someone with a walkie-talkie who, like most ham radio operators, was just hoping to make a new contact.

“This is W0ORE in Space Shuttle Challenger,” England replied. “How are you today?”

This is W0ORE in Space Shuttle Challenger. How are you today?

Tony England, Dean of the College of Engineering and Computer Science at U-M Dearborn, Professor of ECE, and former NASA Astronaut

William Becher, an adjunct professor in ECE and active club supporter, says that for him, the most interesting aspect of ham radio isn’t the communication possibilities but rather the engineering challenges of building radios, accessories, and antennas. In fact, Becher and his wife, Helen, both radio amateurs, assembled and installed the large antenna on top of the EECS building. It was the second one they built, for the first one was even bigger, and the university was concerned that it would be too heavy for the roof.

Another benefit of the club is that, unlike other campus organizations, the UMARC involves people from many different generations. Students are able to network with faculty, staff, and alumni while gaining technical expertise.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“Ham offers a lot, but it can be kind of overwhelming when you get into it, because it’s so much information,” DesErmia says. “It’s really nice having people who have done it to help guide you.”

The club is open to anyone to join. At the monthly meetings, experienced operators go over different topics and provide trainings. They also help people who want to increase their license (there are three levels) in order to use more advanced equipment.

In addition to the many events club members participate in during the year, perhaps the most important is their annual competition against the Michigan State University Amateur Radio Club. This competition, like many others, includes making as many connections as possible in a certain time frame.

“It’s an exciting hobby,” DesErmia says, “because you can pretty much do whatever you want.”

UMARC is currently advised by ECE Professor Amir Mortazawi. To learn more about the club, visit their website.

MENU

MENU